Here’s an English translation of Liszt’s letter, together with some historical context and commentary on why it’s so notable:

Translation

Sir,

I am even more directly interested than most of my honorable colleagues in the success of your ingenious invention. The Chyrogymnaste (apart from its other advantages, which cannot fail to be recognized by all teachers) strikes me as truly destined to make possible— for the majority of pianists—the execution of a certain kind of composition now all the rage.

So do not be surprised if, before long, the publishers of the works of Messrs. Chopin, Thalberg, Henselt, Döhler, etc., include with their new compositions a copy of the Chyrogymnaste as a means of practicing them.

Please accept, my dear Sir, the expression of my most distinguished and devoted sentiments.

Paris, 1 September 1842

F. Liszt

Why This Letter Matters

-

Liszt’s Embrace of Mechanical Finger-Gymnastics

By 1842 Liszt was at the height of his fame—and hypersensitive to any tool that could extend pianistic technique. His enthusiastic recommendation of Casimir Martin’s “Chyrogymnaste” underscores how seriously the era took mechanical aids to technical mastery. -

Chopin’s (Rare) Endorsement

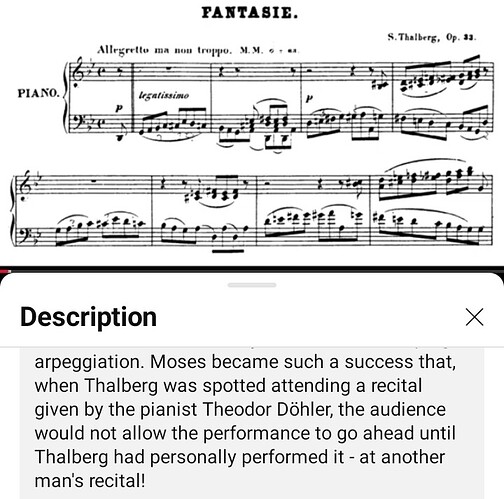

The advertisement for the Chyrogymnaste lists Frédéric Chopin alongside Liszt, Thalberg, Henselt, Döhler, and others:“Thalberg, Liszt, Dohler, Prudent, Zimmermann, Adam, Cramer, Hunten, Chopin, etc., have seen and approved…”

Chopin almost never endorsed public inventions or gadgets—he disliked “starification” and avoided publicity—so his implicit approval here is exceptionally rare. -

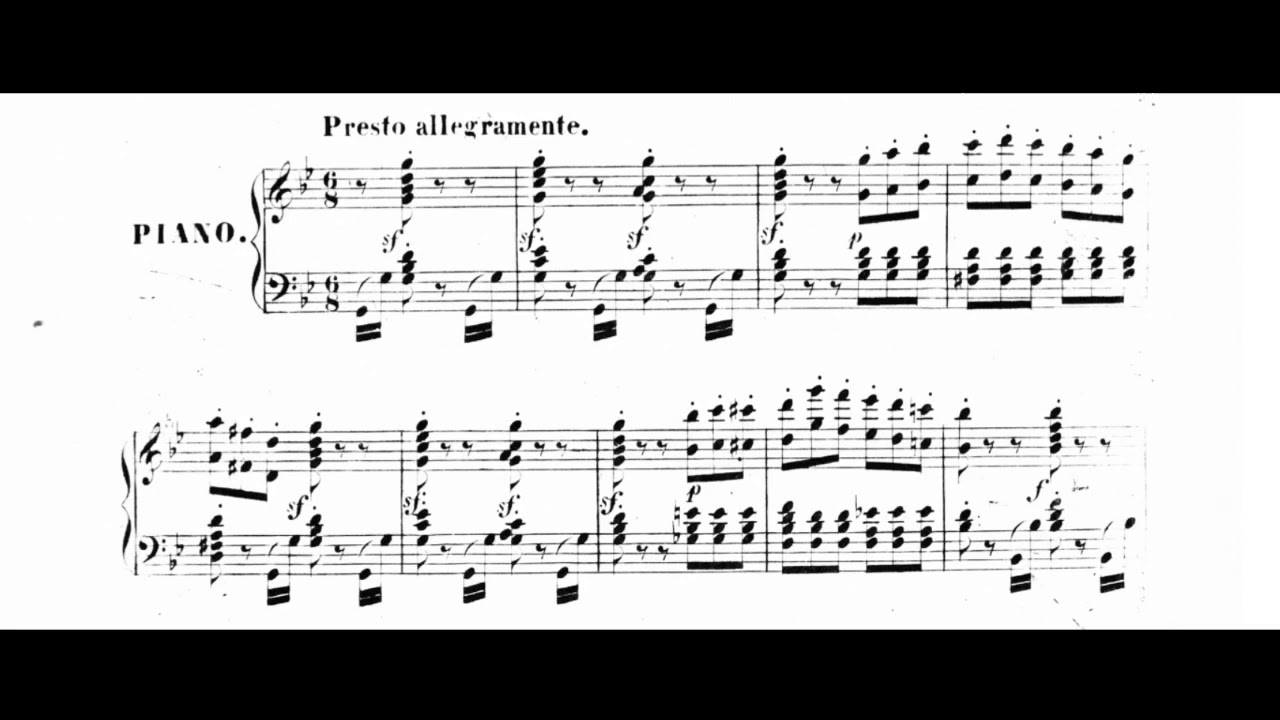

Competitive Virtuosity in the 1840s

Liszt’s letter comes just five years after his famous “duel” with Thalberg (1837), and during a French concert scene obsessed with technical display. By suggesting that publishers bundle the device with new works by Chopin and company, Liszt is effectively predicting—and shaping—a market for ever more demanding repertoire. -

The Chyrogymnaste in Historical Perspective

- What it was: A hand-exercise apparatus designed to strengthen weak fingers and equalize the agility of all five digits.

- How it was used: Students would work through a series of finger-gymnastics routines before tackling high-virtuosic études or concert pieces.

- Legacy: Although today largely forgotten, devices like the Chyrogymnaste show how 19th-century pedagogues sought mechanical shortcuts to what previously took years of purely musical study.

In sum, this letter illustrates Liszt’s forward-thinking embrace of technical innovation, the exceptional—and quite unusual—name-check of Chopin in the device’s promotion, and the feverish culture of virtuosity in 1840s Paris. It’s a wonderful snapshot of how even the greatest artists were eager for any advantage—mechanical or musical—that could push the art of piano playing further.